Community Development Guides

Why Does Community Matter?

We thrive in meaningful relationships, and community is the context where we give and receive. Everyone is wired and inspired differently, and no single person has it all figured out. We’re better together. It is in doing life with others that we become our best selves. We play different roles in society that are complementary to one another.

When everyone takes ownership of their respective parts and leverages shared strengths, we can inspire positive change, imagine new solutions, and resolve issues within and beyond our communities. Our collective impact as an empowered and collaborative community is incredible. Hand in hand, we make the difference we want to see in our world.

Together, we build a City of Good.

The beginner’s guide to community building

Consider your usual routine. (Or at least, the way it used to be before Covid-19.)

Maybe you have breakfast at home or grab a quick bite at a kopitiam. You commute to work or school. At night, you go to a recreation centre to exercise or to a library to work on projects. You catch up on conversations in several online groups and chat rooms. During weekends, you take your family to the park, play sports with your friends, join meetups, or attend an event or a church service.

In each activity, you are participating in and shaping a community, whether or not you see it that way. You might even play a major role in building or guiding the community.

The reality is that all of us belong to at least one community. In a seemingly individualistic society like Singapore, you might not feel this – but it’s true. And the things you do every day can influence these different communities.

On the other hand, you may be conscious of the fact that communities exist wherever you go. But ever wondered what exactly a community is – and how you can contribute?

You’ve come to the right place.

Whether you’re a community member or consider yourself a community developer, it’s important to build a consciousness of the different types of communities around you, what these communities comprise, and the various possible ways you can contribute to them.

We’ll be discussing these in a series of articles, which are based on conversations we’ve had with the developers of various types of communities around Singapore.

But first, a note—this series aims to help you think about communities. It will give you ideas and perspectives on building, assessing, or improving a community. It won’t give you a prescriptive answer on how to develop and solve your specific community’s problems, because every group of people—along with the interests, causes, and problems that bind them together—is unique.

With that said, let’s begin.

Defining community

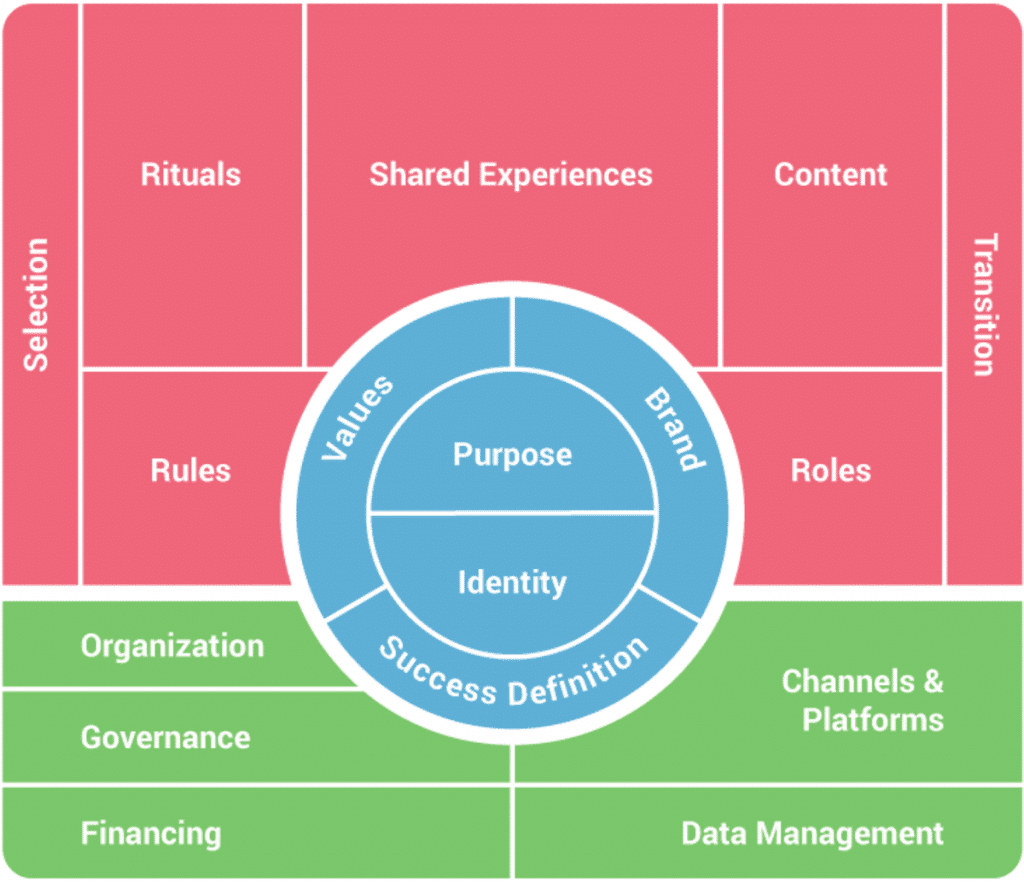

The Community Canvas framework

8 key components of community

Read on to learn about the 8 key components of communities that NVPC has identified through in-depth discussions with community developers across Singapore.

7 perspectives of community development

Where do you go from here?

- Talk to other community members and developers to understand different experiences and perspectives on community engagement and development.

- Study resources on core community components, including Developers, Members, Culture, and Success.

- Answer the reflection questions on each of the resource pages to identify areas to change for the better.

- Read up on how other Singaporeans are developing and improving communities.

- Find a support group of people who share the same interests and vision.

Understanding the role of developers in community-building

The concept of community is complex. Communities can be as broad as an ecosystem-wide organisation for social development, or as simple as a Facebook community page for bookworms to share their thoughts.

They can have an internal or external purpose, or even both.

- Internal purpose — a community that exists to take care of itself, whether that’s supporting one another, learning from each other, or growing the community to a certain number.

- External purpose — a community that exists to pursue an external goal, like fundraising for children with disabilities.

Communities are made up of people with varying perspectives, identities, and attitudes towards how things should be done within the community or what direction the community should be headed towards. Communities can even exist on different scales, with sub-communities existing within a larger one.

With so many variations and moving parts, how can communities function in a way that’s both purposeful and organised?

This is where developers come in.

Community developers, or simply “developers”, are seen as a key pillar to community development. They may not have a formal title, but play a role in steering the community in the desired direction, based on the community’s vision and purpose.

But to properly define a community developer’s role is as complex as defining communities themselves. Each community has its own unique nature, purpose, and members, which all contribute to the overall task of the developer.

Developers themselves view their role from various perspectives. Some may take an ecosystem-wide approach, while others may take a more member-centric perspective. This may also be shaped by the sector in which the community exists such as in the social or commercial space.

To better understand the role of developers within different communities, we talked to several community developers in Singapore to get their personal insight on their role and will discuss three themes in this article:

- 1. The many facets of a community developer

- 2. What a community developer is, by what s/he is not

- 3. Community developers do what’s best for the community

The many facets of a community developer

As expected, community developers refer to themselves and the work they do differently. There was no one job description or term they could agree upon, as each term held different meanings, connotations, and associations based within the context they’re applied to.

Bee Leng, a developer from local charity AMKFSC Community Services, even said that she preferred using “new names” to help people think about their roles differently.

Some referred to their roles as “facilitators”, “animators”, or “alongsiders”. One even described developers as “octopi”—people who are doing a million things at once.

To grasp this terminology, let’s take a closer look at how developers view their responsibilities:

Community developers expand their members’ capacity to aspire

Some developers described their role within the community as one that helps members expand their capacity to aspire beyond existing scopes and situations.

One developer used the term “painter” to describe this role to illustrate painting a big picture—or one that is larger than the current boundaries of the community. The painter sees possibilities that members might not otherwise see or dream of, and through thoughtful facilitating, guides the brush strokes to realise that painting.

Another used the term “innovator”, to convey their role as a designer of a community that learns together so members are empowered by their knowledge to increase their capabilities beyond what was perceived.

Community developers build their members’ potential to achieve their goals

Similarly, there were developers who described their role as enabling their members to achieve their goals through capacity building or providing opportunities that allow them to do so.

A “capacity builder” builds the skills, confidence, and expertise of members to achieve their goals. Meanwhile, “enablers” or “catalysts” are those that empower members within the community to use their individual strengths to do good within their community and pursue the goals and causes they care about.

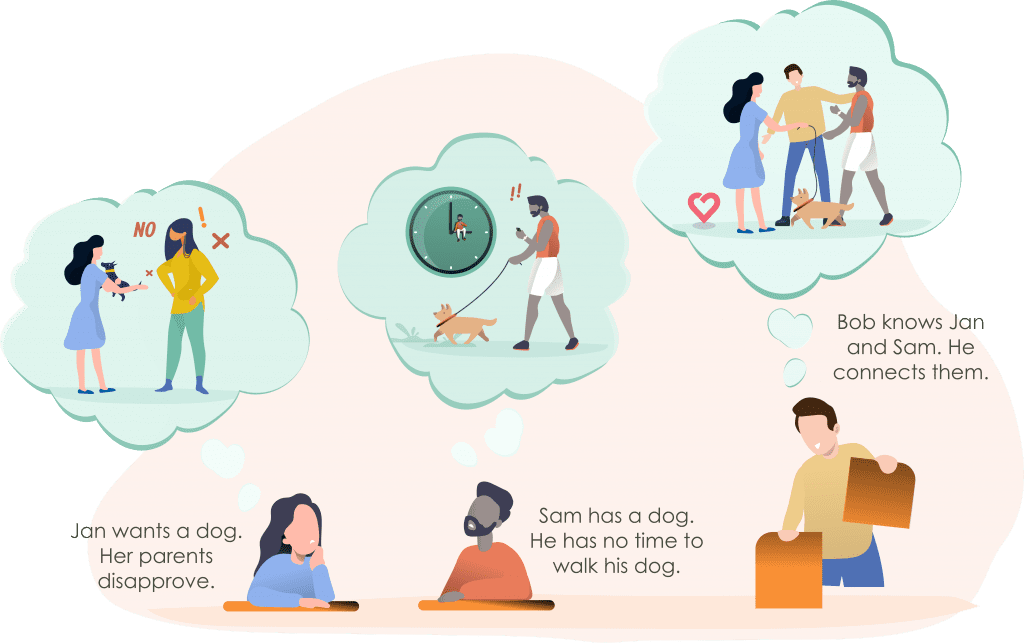

Community developers bridge and discover assets in the community

Several developers described their role as a “bridge” or “connector”, discovering assets and strengths in and beyond the community, and linking these assets to those who need it. Members of the community can be “bridges” and “connectors” as well.

Another developer described their role as a “treasure hunter” as they find treasures (like skills, resources, and opportunities) within (e.g. volunteers) and outside (e.g. partnerships) the community where they might not be so obvious.

Community developers do multiple things at the same time

One community developer described his role in the community as being an “octopus” because of the many roles developers play, including cheerleader, safety net, signpost, historian, mirror, and architect. In this perspective, developers wear many hats as many things need to be done in different facets of a community.

Community developers are personally engaged with the community

One described the developer’s role as “Kaypoh”, a colloquial term used to describe a nosy person. Developers need to make an effort to learn about the lives of other members to help them create lasting internal changes throughout their stay in the community. Journeying with members and building relationships help keep the community together.

Another developer referred to his role as an “explorer”, as he “digs around” to get to know members better, listening to them and understanding what they are passionate about. In effect, he builds relationships with them too.

Community developers are mindful that communities are already present and may not necessarily need to be “built”

A developer expressed unease with the word “developer” as it implied that their role was to build something new when in some contexts, communities preexist and any outcomes were the result of previous member interactions.

He suggested the term “animator” as a more appropriate term to highlight the role that developers play in bringing a community to life. The animator shows up collaboratively and enables, supports, and facilitates; shifting the power of developing the community to its members.

Another developer described his role as a “contributor”, emphasising the fact that everyone contributes to the community in his or her own way, and the developer is simply one of the many contributors in the group. In this sense, contributors focus on the needs of the individual rather than the institution.

Though, in some cases, communities do not necessarily need the help of the developer. If a developer is not wary of this, “intruding” in that community could potentially “kill their spirit”.

Some community developers provide professional services

There are developers who play dual roles—one as a professional and the other as a community developer. Developers who have to wear professional hats shared that they could not “run away” from this identity as members saw them as professionals and held expectations for these developers to provide solutions for their immediate needs.

These expectations create a barrier, preventing developers from playing other potentially personal roles in the community.

What a community developer is, by what s/he is not

With all that said, is there any point in trying to define a developer’s role?

While all the developers saw their role as something unique to their community, they agreed on a number of things they believed a community developer is not.

A community developer can be a “leader”, but not in the sense that implies hierarchy and power; as if the developer were the sole decision-maker of the community and members are disempowered to act. Neither is a developer someone who has “control” over the community and can intervene and veto decisions whenever he or she pleases.

Rather, a community developer can be seen as a servant leader—someone who serves rather than controls. An “animator”, “facilitator”, or “alongsider”, or simply put someone who brings the community to life; someone who gently “prods” and “suggests” rather than makes all the decisions.

A developer must be comfortable with ambiguity and willing to have “incomplete control” whilst watching over the community. Furthermore, the developer must acknowledge that communities may already be present and not necessarily “built.”

Community developers exist because it’s difficult for communities to grow organically without any direction. There is an abundance of diversity within communities, and developers must bring the focus to the similarities—to the shared vision, purpose, and goal of the overarching community.

In no way does the developer “own” the community. In fact, many developers hope to someday exit the community. If he or she owns the community, then the community will be lost upon the developer’s exit.

Through intentional facilitation, developers can instead create a sense of ownership among members and encourage them to take leadership roles within the community. In that way, developers are also cultivating future developers from within the community.

Member development journeys can guide developers in creating that sense of ownership. This includes:

- Onboarding and induction SOPs, which are constantly revised through conversation and feedback

- Ground rules for managing conflicts and setting expectations of behaviour and conduct

- Named misbehaviours as members may not know they are behaving in a contrary way

These rules and guidelines provide structure and reinforce the values of the community.

Community developers do what’s best for the community

At the end of the day, the role of a developer is a broad one that serves to reflect the goals of the community as a whole. While they go by many names, developers need to give space for communities to realise their own potential and take a back seat when community members step up, allowing the community to come up with solutions and bring new people into the community as well.

Community members are certainly not just beneficiaries of the community, they are part of what makes the community alive. They may require some guidance from the developer at first, but they may also find it in themselves to become developers themselves.

With that said, anybody can be a developer! Just take note of some of the qualities that would be helpful to have:

- Communication skills

- Relationship-building skills

- Interpersonal skills

- Compassion and empathy

- Organisational skills

The road to a thriving community

At the heart of any community is its members—the people who live, learn, and contribute within a group that shares similar interests, identities, or missions.

When those members feel comfortable with one another, are open to giving and receiving, possess a sense of ownership over the community and are making progress towards their goals, then it can be said that the community is healthy.

Every developer wants to help their communities thrive. In order to do that, there are four things they should consider doing:

Foster a sense of belonging and inclusion

A “sense of belonging” happens for different reasons for different people and on different scales. Some members will feel more at home with the group than others, depending on factors like how long they’ve been members, how much they’ve contributed, and how aligned that community is with their own purpose. To understand how you can encourage inclusion within the community, you need to know the different ways members develop a sense of belonging:

- When members have a common vision and goal they would like to achieve.

- When existing members are friendly and create a welcoming environment. This helps new members become comfortable in the environment and encourages them to make friends.

- When members meet up regularly. Regular meetups help build relationships within the community as they give members an avenue to familiarise themselves with one another and deepen friendships. Some communities even have designated “befrienders” for these meetups.

- When members’ opinions and feedback are heard This allows members to feel valued and appreciated, but most importantly, seen. Particularly, developers should be intentional in reaching out to minority groups, whose voices are often overlooked or neglected. When members know that their voices matter, they will feel comfortable in the community’s space.

- When members are given the ability to make decisions and enact their ownership over the community. Members who help make important decisions or contribute their talents for the development of the community are more likely to feel attuned to the community’s overall purpose, which lends to his or her sense of belonging.

All of these scenarios can be understood within the context of “inclusion” and “exclusion.” While these might seem like basic concepts, there are certain nuances to consider. Inclusion can take the form of racial, religious, gender, or abilities. Others consider inclusion in terms of participation as a member can feel “included” even if he or she is unwilling to participate or be actively involved in contributing to the community.

A community will have groups with varying levels of inclusion, and that’s okay. Developers can define inclusion in terms relevant to their community to manage expectations.

While exclusion sounds like a bad thing, it may be necessary to exclude certain people in order to fulfill specific purposes shaped by the boundaries of the community. If a community is too diverse, members end up with very little in common, making crafting programs a difficult endeavour.

For example, Friendzone.sg organises community gatherings for young adults ages +/- 18-35 (in the life stage of tertiary education, NS, or fresh in the workforce). The purpose of setting these boundaries is to attract and build a community of youths in this specific age range of participants within the neighbourhood as opposed to organising neighbourhood activities for all ages. They tailor their programmes and activities to this demographic.

In cases where exclusion of members is necessary, developers need to be able to communicate the need to exclude certain members. Pal, a community developer for South Central Community Family Service Center, shared how situations where members have to be excluded are handled —he calls it the “3 E’s”. This should be a collective decision by the group and not by the community developer. He explains, “our role is to enable the group to facilitate decision making and execution.

- Personally engage the member/s that the group feels need to be excluded (for now). We are not banning this member but saying that, for now their presence is, for whatever reason, not contributing positively or appreciated.

- Explain why the group feels that the member/s cannot be included for now. Be specific, e.g. what was it about their actions, behaviours, character or etc.

- The group must articulate expectations clearly to the member/s, as to what is expected of them to be accepted by the group. This would help in suggesting that there is always an avenue to return if the member/s is ready for change.”

Develop community ownership

For communities that involve a provided programme or service by an organisation, there is a danger of members seeing the community as merely a commodity—something they take or receive from rather than something they are a part of or give to.

If your goal is to create a healthy community, then this isn’t the way to go. Developing a sense of ownership of the community among members ensures that there exists the drive to sustain itself even when resources are low or developers or facilitators are absent.

If your goal is to create a self-sufficient community, then you need to develop a sense of ownership among members—whether or not the community revolves around a program or service—to ensure that the community can sustain itself even when resources are low or developers or facilitators are absent.

But firstly, to own something, one has to perceive that the thing belongs to you. Members must believe that they belong to the community and the community belongs to them.

Secondly, there must be clarity and understanding of a member’s role – i.e. what contributions or responsibilities are expected to be fulfilled and what rewards will be received in return.

Ownership occurs at different scales such as the intrapersonal, interpersonal, intra community and intercommunity. At an intrapersonal level, this looks like the individual seeing and understanding their role in their community. In this lens, one can take ownership in the form of overlaying one’s personal goals with the change one wants to drive for.

At an interpersonal level, it refers to the relationships one has with others. For example, the intentionality an individual takes to build and deepen relationships or welcome others. Strengthening relationships with each other motivates individuals to play an active role in building the community through delivering programs or shaping the culture.

On an intercommunity level, ownership could look like an individual identifying ways to bridge the different communities they are a part of. For example, performing with dance friends at the senior activity center that this individual volunteers at; or inviting friends from different communities to experience and understand the culture of another community.

Many factors can contribute to cultivating ownership, such as meeting frequently so friendships are formed, knowledge is shared and contribution is slowly normalised. Developers should also listen to members and understand what they would like to learn or how they would want to contribute. Cultivating a sense of ownership should also be accompanied by practice systems or set structures that would act as a means to encourage commitment, scaffold responsibility and ensure members treat each other respectfully.

Developers from Yishun Health run a programme that helps seniors prevent frailty through exercise. The community developer was very intentional in ensuring the programme could run even without them being present, so they taught “Leaders”’ among the community how to do these exercises and how to teach others these exercises as well. Sometimes, the developer would intentionally be late to see if members would run the programme themselves. This way, the developer is able to prepare the members for his eventual exit from the community; and act consciously as “catalysts” or “animators” to the community.

In contexts where the developer’s purpose is to build a sense of ownership among members and leave the community shortly after, developers may need to be “friendly but not a friend” to prevent members from becoming too dependent in a way that’s understood in “normal friendship.”

Using the same example from Yishun Health, we can identify two ways to develop ownership:

- Developing ownership through value. The senior citizens were given a role to play in the community, which made them active participants in the growth and development of the community. This gives them a sense of responsibility in running the program and ensuring their fellow elders had the proper exercises to keep them strong.

- Developing ownership through contribution. Ownership and contribution go hand-in-hand—the more members contribute, the more they will feel a sense of ownership over the community, and vice versa.

However, take note that not all communities are ready or willing or able to take ownership. Elysa from Campus Impact, a non-profit organisation that runs programmes for youths who are going through a transitional phase in their lives, shared the difficulties she had in getting the children to take over or helm a programme. Recounting one instance, Campus Impact had given the children the opportunity and space to run a programme but immediately had to intervene because conflicts arose among them.

At the end of the day, ownership is not a linear process, but rather an iterative one. The ways in which developers encourage ownership within their communities are largely governed by intuition rather than theory, which is why so many find it difficult to pass on ownership of the community to members rather than outsiders.

For developers who plan on leaving their communities eventually, this is essential for the community to survive. Former community members can step up to take on various roles to continue nurturing the community, take the lead and become new community developers instead.

But there’s no doubt that members who have a strong sense of ownership over their communities are more self-sufficient than those who don’t.

Encourage community contribution

In community development, there’s an approach called asset-based community development (ABCD) that involves paying attention to what is in a local place (not what we think should be there or what isn’t there) and believes in discovering assets currently present in the community and using those assets for the benefit of the greater community.

In this approach, members are viewed as “active citizens” rather than “passive recipients”—people who are capable of contributing and are empowered to rally together to solve community problems.

There are three factors that affect a member’s ability to contribute:

1. The member’s capacity and means

Each member has a different assets to contribute—it could be a skill or talent (e.g. the ability to host a community event), stories or experiences (e.g. an inspiring tale of overcoming adversity), professional background (e.g. background in graphic design to help with social media pushes), or resources (e.g. a house to contribute during community retreats).

Every member will contribute differently so it’s important for developers to identify and assess what kind of assets are present within the community, who can contribute these, and how much members are willing to contribute.

Ways developers can do this include having continued individual conversations with community members, asking members to provide background information during the member’s registration process, posting a call for volunteers or sending out surveys.

2. The structure provided by the group

Are there avenues for your community to contribute? Providing proper communication or contribution channels is essential in enabling your members to contribute in the first place.

Elysa from Campus Impact shared that to encourage contribution within her community, she provides a duty roster for the youths who come to the Centre. Within the roster, she allows members to initiate any other channels of contribution they deem fit, as well as provide feedback on existing initiatives.

Rather than just sending members a laundry list of items to contribute, Elysa gives members an avenue to be heard and involved in the community’s decision-making processes. And this, in turn, promotes ownership among members.

3. Affirmation given for each contribution

Whatever the structure, it’s important to affirm member contributions to ensure they have a positive experience giving back to the community. Hopefully, this appreciation encourages them to continue these efforts in the future.

Affirmations can be as simple as thanking volunteers publicly, through a social media post or even a public announcement. Or it can be personal affirmations through tokens of gratitude and appreciation.

It’s important to note, however, that not all member contributions will result in positive outcomes, so you need to be prepared to manage or address that, and decide how involved you want to be should conflicts arise.

Contribution takes time

Members are more likely to contribute if they feel a sense of belonging and their personal interests are fulfilled before they feel comfortable enough to actively contribute. A welcoming and inclusive environment also helps.

Willingness to contribute is likened to going through a series of doors—members will only open a door when they’re ready. And empowering members to move from one state to another requires investments in time and effort, but it’s all part of a much larger goal of cultivating a sense of ownership.

Manage diversity among members

Earlier we talked about the role of inclusion and exclusion within communities. Usually, communities are united by a common purpose—whether it’s to join a program that offers a unique skill or benefit, or having a common interest. Even if you were to be as exclusive about the kind of members you want to join the group, there will undoubtedly be some level of diversity among members.

Members have different demographics, skills, and reasons for joining a community. And more often than not, that’s a good thing. But differences between groups can naturally bring about conflicts of interest. For example, your community might have similar interests or goals but have entirely different approaches to that end.

Identify the common cause, identity, and interest between members

Developers agree that identifying the needs and interests of members can pave the way for a sweet middle-ground when conflict arises.

Company of Good, a community dedicated to empowering Singapore businesses to give, makes time to engage inactive members of their community to understand how they can help them meet their needs.

Understanding both engaged and unengaged members can prove to be an enlightening experience for the developer and provide ideas on how to better the overall betterment of your community. Mandy explains: “Understanding the unengaged could help us understand their motivation of being in a community. For example, some are interested in networking and meeting new people, some are interested in learning a new skill while others return because of the friendship in the community. A community can develop a range of offerings to continuously engage people with the same purpose (but different commitment level and different hook points).”

“Meanwhile, this exercise also helps potential members discover for themselves what aspect of the community interests them before they even join the community. Lex from co-working space Mutual Works says this is what his community does to better gauge how the members might enjoy being part of the community.

Overcoming the challenges of diversity

To find that “middle ground” between members, developers need to focus on commonalities within the community. When different members of the community have a common cause, identity, or interest, redirecting the conversation towards these similarities can remove biases and instil a sense of solidarity.

Provide avenues or “safe spaces” for members to discuss their diversity openly with others

Managing diversity can only happen if members have a space to discuss these issues. Developers also need to be adaptive to differences and make time to listen to members, allowing them to be heard and helping them accept and respect each other’s interests and needs.

Again, this requires having a welcoming environment that encourages candid conversations and honesty.

Abhishek from Beyond Social Services shares about his experience managing diversity. He says that when a conflict in the community becomes too disruptive, developers will approach the members who are involved and ask if they would like to work on it on their own. If there is still conflict, the developers will suggest a peace-making circle where involved members can take turns to share their feelings and thoughts on the issue, bearing in mind that the objective is to understand and make peace.

The role of the developer is not to get involved, but to maintain a safe circle for peace-making to occur, even if that means reaching an outcome where members go their separate ways.

This kind of culture should create norms rather than rules. Rules are set and limiting, and often created without dispute from members, while norms are the result of dialogue and understanding.

Norms are also much more flexible—like a guideline more than anything—and can contribute to a greater culture of collaboration and cooperation. After all, members are abiding by these norms of their own volition, and that solidifies the respect they have for each other’s differences.

Building an active, engaged, and inclusive community

Just like cultivating ownership, community-building is an iterative process that requires a lot of trial-and-error and customisation on the part of the developer. Every community is unique—it will have its own set of members, assets, contributions, and even conflicts that developers will have to draw on past knowledge and experience to navigate, manage and adapt accordingly.

Developers, too, have their own views on what a “successful” community is, as well as their own opinions and best practices on how to create a thriving and self-sufficient community.

But developers can agree that the key to creating active and engaged members is through:

- Fostering a sense of belonging and inclusion by focusing on common goals, welcoming new members, meeting up regularly, and getting members to contribute and feel a sense of ownership over the community

- Developing community ownership by giving members a role to play in the community and opportunities to contribute

- Encouraging community contribution by giving members the freedom to initiate and suggest, providing the right structures to make contributions possible, and to give consistent affirmations for contributions

- Managing diversity amongst members by creating safe spaces for dialogue and focusing on similarities among members

To incorporate all these concepts into strategies for developing your community, we suggest you take a closer look at the membership journey. You can find a template for curating your own membership journey here (Coming in December 2020).

The challenges of culture-building within communities

Culture can make a community member decide whether to stay or leave. It can help them achieve their vision or hold them back constantly. It also affects the way members see themselves within the community.

Yet for all its influence and importance, many of us are hardly aware of how we practice, form, and spread our culture.

Students of culture like to ask: “Do fish know they’re in the water?” The idea is that we are so immersed in our culture, we are barely conscious of how it influences our every word and action.

Some people don’t like this metaphor—but they don’t necessarily disagree with its point. Try to recall how many times you’ve asked a question and the answer was a blank stare and the feeble explanation: “Because we’ve always done it that way”?

As a community developer or active member, we’re betting that’s not the type of statement you’d want to make when talking about culture. You’d rather have an answer with more self-awareness, just like fish becoming “aware of the water in which it swims”.

We hope this piece will help you think critically about culture within communities and inspire you to shape your community’s culture for the better.

Why we need to talk about culture in communities

We gathered developers from various types of communities in Singapore and asked them to talk about culture within their communities.

These developers agreed that culture is the most important aspect of why people enter and participate in a community. That means culture can make people decide to quit a community as well.

Consider, for example, how many employees leave companies because of “toxic cultures”. A majority (95%) of human resource leaders say burnout causes employees to quit.

Or try to remember the last time you thought of moving to a different neighbourhood. Aside from the price of rent, you probably evaluated people’s lifestyles and the area’s physical attributes, and how these fit into your personality and aspirations.

Finally, think about how you ended up becoming a developer or active member in a certain community. You may have joined for different reasons, but what motivates you to stay? Do you feel that you belong?

If so, you have culture to thank for that.

1. Defining culture in the context of communities

2. Cultural tensions in communities

3. Can you really change a community’s culture?

Culture is complex, but trust can be the glue that reinforces it

As it affects all aspects of our lives, culture is a very complex web to trace. And parts of it can change slightly everyday, whether it’s caused by external forces (see: The Rona) or by internal events and relationships.

It’s impossible to keep a culture “under control”—and you shouldn’t even try. While you can reinforce your community’s culture through stories, experiences, physical symbols, and shared values and goals, you need to embrace its complexity and dynamism. As one Singaporean developer pointed out: “Magic is in the mess.”

Instead, allow trust between people in the community to uphold and preserve the best parts of your culture, and to transform it when the need arises. By focusing on building trust, you can take a step back and see the community growing and gaining strength on its own.

If you’re interested in learning more about how to understand and measure success in your community, read on to our next chapter: Defining Success within Communities.

Defining “success” within communities

What does a “successful community” look like?

For some people, it means having a safe space where they can share a common purpose and values with like-minded individuals—think of a group of board game enthusiasts who play a couple of rounds of Dungeons & Dragons on weekends. For others, it’s about having healthy and diverse participation under good leadership. You can see this in professional societies and civic groups in Singapore. These examples underscore the fact that community success is a fluid concept—one with many faces depending on your community.

Whatever the case, it’s clear that defining the success of a community ultimately rests in the hands of its members and key stakeholders (more on this later). If you’re a community developer, your challenge is to figure out what goals and objectives your community should achieve for it to be “successful.”

Generally speaking, there are two ways to go about doing this:

- External — You can look outside the community for goals you can work on as a whole. For example, a group of bike commuters can petition the government to have more bike lanes in the city. Achieving this goal provides community members with a clear target they can focus their efforts on.

- Internal — You can also look inside your community for worthwhile outcomes. For example, your objective might be to strengthen your community members’ relationships with each other. You could also focus on engendering a culture of member contribution.

In this series of articles on defining community success, we’ll be talking about what the developers behind some of Singapore’s thriving communities think success means, why community success is so subjective, and how to measure success within your own communities.

Should community developers be measuring success?

Identifying KPIs or metrics for community success

5 examples of community success measurements

How to engage your community to uncover success metrics

Remember, success is subjective

At the end of the day, it’s important for developers to create metrics that allow them to keep track of the community’s growth and development as well as ensure that the community is heading in the right direction, depending on its core goals.

However, it’s also important to remember that the nature of community work is fluid—communities can form and collapse spontaneously, and people will come and go. The clarity in community work is always evolving and the “right” thing to do will change at some point or another.

Bottom line? There is no singular definition of success and the definition of success agreed upon should be flexible enough to adapt.

Where Do You Go From Here?

If this is the first piece you’re reading from the Community Matters series, we hope that you gained some fresh perspectives that broadened your views on community. Do have a read of the other resources on community components such as Community 101, Developers, Members, and Culture.

You may wish to learn from how other Singapore are nurturing their various communities.

Finally, reach out to the NVPC Community Matters team to join in our monthly topical events on community life at [email protected].

Wishing you all the best in your community development journey!